Powerlifting through Hysteresis

On strength lost, strength regained, and the scars that shape an economy.

This week on Macro Musings, I talked with Peter Conti-Brown and Sean Vanatta about their new book, Private Finance, Public Power: A History of Bank Supervision in America. The book is a richly detailed history of how bank risk has been managed from the antebellum period through the Civil War to the Great Depression and beyond.

The story they tell is one where U.S. bank supervision evolved not through grand design but through institutional give-and-take between public and private actors in what the authors call “institutionalized discretion”. Over time, this improvisational process has tilted toward greater federal responsibility for financial system resiliency, with supervision becoming the primary means through which that responsibility is exercised.

This is a timely discussion. One of the most important and unresolved questions in bank supervision today is how much failure we should be willing to tolerate in the banking system. So I asked Peter: how should policymakers decide when to let a bank fail and when to step in? His answer pulled no punches:

My cynical answer is, your intuition about how much failure is appropriate—I’m speaking to the bank regulators—it needs to be increased. You need to be much more tolerant of failure. This isn’t just hindsight bias, as you know, I have talked about on this show before. I think the Fed and Treasury and FDIC mishandled the 2023 crisis in about seven different ways. I’ve thought that throughout. There is a new piece by Jonathan Rose and Steven Kelly that, I think, is probably the single best piece of writing on the 2023 crisis that really goes through this argument that you’re talking about… I think we can say that the Biden administration’s tolerance for bank failure should have been expanded. It was way too low.

What makes Peter’s answer so interesting is that regulators themselves seem to be embracing this message. In her first speech as the new Fed Vice Chair for Supervision, Michelle Bowman echoed the same theme:

“The task of policymakers and regulators is not to eliminate risk from the banking system, but rather to ensure that risk is appropriately and effectively managed… Our goal should not be to prevent banks from failing or even eliminate the risk that they will. Our goal should be to make banks safe to fail…”

Bowman may or may not have read Private Finance, Public Power, but her remarks could have been lifted straight from it. Either way, the alignment is striking and a good reason to listen to the podcast if you want a glimpse of where supervisory thinking might be heading next.

By now, you are probably wondering about the title of this post. While the podcast is largely about bank supervision history and its implications for today, we also had a fun conversation about powerlifting! Yes, you read that correctly. Peter is quite the powerlifter and got into it because of Sean. In the video clip below, we discuss their powerlifting journey and how it connects to the notion of economic hysteresis. To shed more light on this idea, I will further unpack hysteresis and its implications for macroeconomic policy in the remainder of the newsletter.

The Powerlifting Analogy for Hysteresis

Our discussion in the video above draws from an earlier Macro Musings podcast with Luca Fornaro who has done important work on economic hysteresis. In that episode, I began our conversation by using Peter’s powerlifting ambitions as an analogy for understanding hysteresis. Specifically, I said the following:

Right now, [Peter] can max out a total of 1,100 pounds. He's aiming for 1,500… let's say he gets there—and then one day he gets incredibly sick. He gets a bad case of pneumonia, he's bedridden for months, he can't do much, his breathing is worse, he loses his strength, muscular atrophy. When he goes back to the gym, he can only get 800 [pounds] total. He goes from 1,500 to 800 [pounds].

Now, let's say he's going to the gym every day. He feels good, his health is restored, but he's lost all that strength. Unless he really pushes hard—he runs the body “hot,” so to speak—he's not going to get back to that peak… He can just go along and maintain… but he would have to work extra hard, [do] extra rigorous training sessions to get back to 1,500.

In my mind, that's a view of what hysteresis is. The economy gets hit with a deep recession, and people—they lose their skills, their capital, their productivity. They're out of their workforce, they're permanently scarred. Even capital is affected because you don't have people coming into work, less demand for factories, and such.

The economy itself can be permanently on a lower… potential GDP growth path. To get it back to where it should be, you have to run the economy hot, just like Peter would have to work extra hard. You'd have to run the economy hot.

Luca agreed this analogy captures the basic intuition of hysteresis quite well, especially as it is understood in recent macroeconomic theory. He emphasized that hysteresis is fundamentally about how temporary downturns can leave lasting scars on the economy’s productive capacity. When demand collapses for long enough, workers stop accumulating skills, firms cut back on investment—including in R&D—and the result is a persistent drag on future growth. It is not just that output falls; the potential for output shrinks. As Luca put it, a deep recession “can cast a long shadow” over an economy’s trajectory even after the initial shock has passed.

A Case Study in Hysteresis

This idea helps explain what happened to the U.S. economy after the Great Recession of 2007–2009. It wasn’t just that real GDP declined; it is that the economy’s potential—what it could sustainably produce—was revised downward as well. The Congressional Budget Office's evolving estimates of potential GDP tell that story.

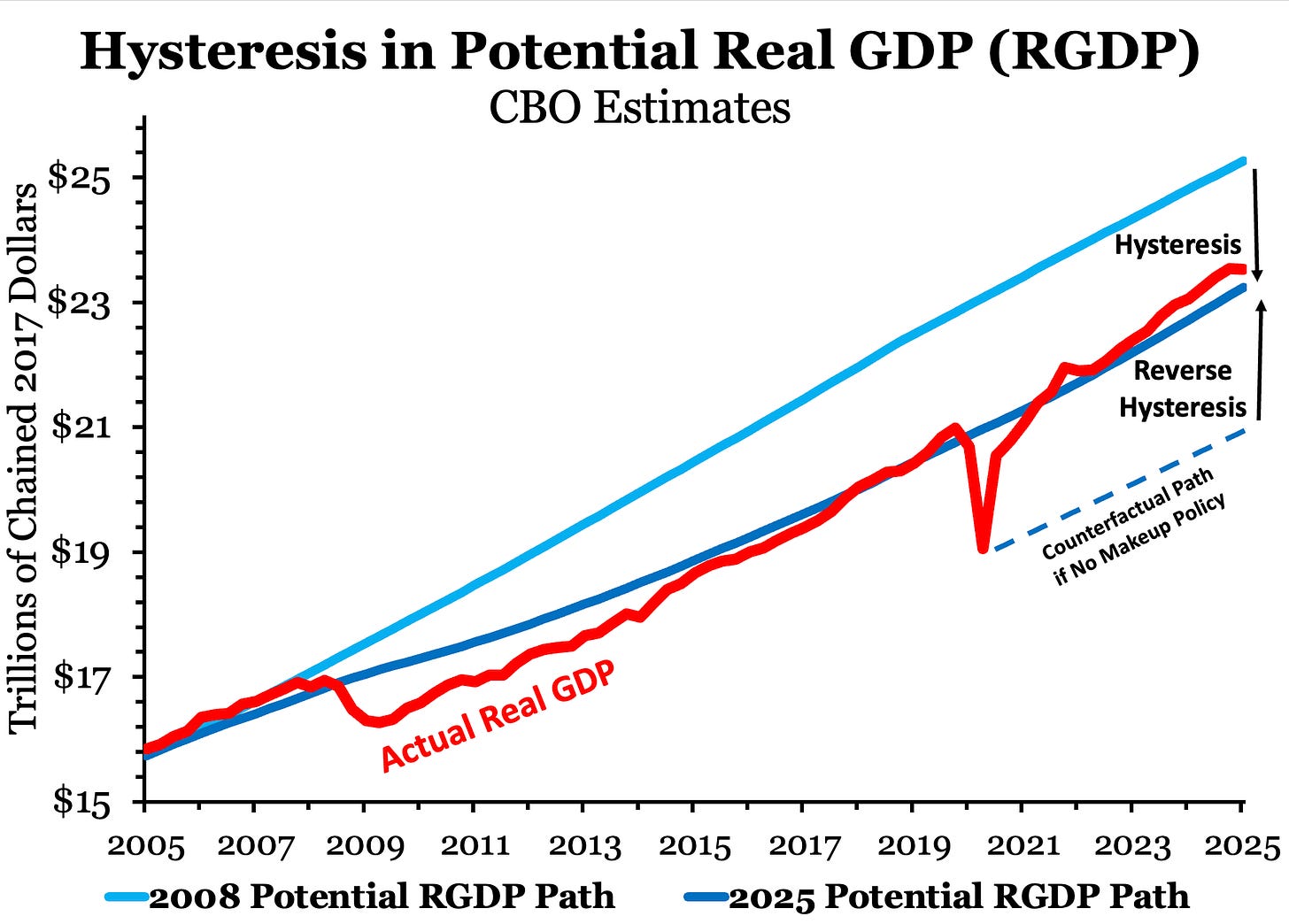

The chart below compares the CBO’s 2008 projection of potential real GDP (in light blue) with its updated 2025 estimate (in dark blue), alongside actual real GDP (in red). The gap between the CBO projected path of potential real GDP and the newer one is a visual representation of hysteresis—how the Great Recession led not just to a temporary dip, but to a long-lasting decline in the economy’s productive capacity. The actual GDP path never caught back up to its pre-crisis trend, suggesting that the damage from the recession extended well beyond the immediate collapse. Skills eroded, investment stalled, and the economy settled onto a lower trajectory. This is Peter’s post-pneumonia gym sessions in macroeconomic terms.

What is especially interesting is what happened after the COVID-19 recession: a rapid recovery and a growth path for potential real GDP that does not decline. That is what the chart labels “reverse hysteresis”, the idea that aggressive macroeconomic policy can return the economy back to its original trend path. Given what happened after 2008, it is not far fetched that the outcome could have been another one of hysteresis—the counterfactual dashed line—had there not been strong support from monetary and fiscal policy.*

Now some readers will object to my claims of reverse hysteresis for the post-pandemic recovery. They will say this was a supply-side recession and it was bound to recover quickly on its own. But even a supply-side crisis, like the pandemic recession, where nominal incomes suddenly collapse can easily metastasize into a severe financial crisis given fixed nominal debt contracts and other financial frictions. A severe financial crisis, in turn, can depress aggregate demand, reduce investment spending, and lower potential real GDP. Luca Fornaro has a JME paper titled The Scars of Supply Shocks that makes this very point.

However, for reverse hysteresis to work, makeup policy may need to be applied quickly, or the lost capacity becomes permanent. That is how I interpret the findings from this interesting study by Oscar Jorda, Sanjay R. Singh, and Alan M. Taylor. They show, using annual data for 17 advanced economies over the period 1900 to 2015, that tightening monetary policy can have a permanent effect on real GDP while loosening monetary policy does not. They conclude that “a central bank might not be able to undo the long-run effects on the economy’s potential by running the economy hot.” I suspect their results are capturing the effects of monetary easing only after the economy’s capacity is permanently lost. What happened in 2020-2022 in the United States was very unique—one of the few times makeup policy or “running the economy hot” was genuinely tried in a timely fashion.

Conclusion

The powerlifting metaphor may be unconventional, but it gets at something central: economic damage from crises isn’t just about what’s visible in the moment, it is about the long shadows they cast on our future potential. Hysteresis reminds us that if we don’t act decisively, recessions can harden into permanent losses. But reverse hysteresis shows us there’s a way back if we are willing to move quickly, take risks, and run the economy hot.

One potential lesson from the pandemic recovery is that reverse hysteresis only works when macroeconomic policy is timely. Waiting too long risks locking in the damage. That’s why systematic makeup policy—policy that automatically kicks in to offset prior shortfalls—is so important. And it is why, in my view, the Fed’s current framework review should not throw out the makeup policy baby with the FAIT bathwater. If we want an economy capable of regaining its strength after a major setback, we need a policy framework that doesn’t just aim for stability, but actively restores what’s been lost.

Bonus Content

*To be clear, the application of makeup policy and “running the economy hot” can be excessive, as was arguably the case in 2020-2022. As I argued in this post, macroeconomic policy should have been aggressive during the pandemic, but better calibrated to the projected growth path of NGDP. Even so, I would encourage critics of this period’s macroeconomic policy to consider not the ideal macroeconomic policy for this period, but what was the likely counterfactual outcome if makeup policy had not been tried. I suspect it would have been ugly.

"They will say this was a supply-side recession and it was bound to recover quickly on its own."

A negative _demand_ shock like 2008 ought to be easier to fix with monetary policy than a supply ide shock. The "Great Recession" was just incredibly bad monetary policy, refusal even to return the price level to a 2% trajectory when even that might not have been enough.

This post provides a visual "explanation".

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/the-simple-and-true-story-of-the