Something interesting—and concerning—is happening. Consumer inflation expectations for the next year have started rising again, just as we seemed tantalizingly close to declaring mission accomplished on the Fed’s 2% inflation target. This worrisome shift can be seen clearly in the figure below:

What explains this turnaround? In this newsletter, I argue that the uptick in inflation expectations shouldn't come as a surprise. The American psyche was deeply scarred by the dramatic inflation surge during the pandemic years. This recent history has left American households highly sensitive to perceived inflationary threats, complicating the Fed's efforts to reliably achieve its 2% inflation goal. It also explains why the current trade war, which is expected to raise consumer prices, could prove even more unsettling than the trade tensions of 2018-2020—and may already be driving the observed rise in inflation expectations shown above. These developments could also have important implications for the upcoming midterm elections. Let's unpack each of these points.

The Scarring of the American Psyche

As we all experienced firsthand, U.S. inflation surged during 2021–2022, peaking at 9% in mid-2022—the highest level in over 40 years—before gradually cooling to just above 2% by late 2024. Still, the cumulative increase in the price level over this period was just over 20%, leaving it about 10% above the path households had anticipated. This left many Americans feeling financially strained and played a significant role in shaping the outcome of the 2024 presidential election. It also left an indelible mark on the American psyche.

So, how do we know the American public has been scarred by inflation? Let’s start with some revealed preferences. First, Google searches for inflation reveal a notable structural shift: people are now searching for the term at a consistently higher level than before the pandemic. Yes, the overall level of searches has declined from its peak, but it remains notably well above pre-2020 levels.

We can explore this structural shift more deeply by comparing search interest to the actual inflation rate in a scatter plot. The figure below does just that and reproduces the findings of Oleg Korenok, David Munro, and Jiayi Chen (2024), which show a threshold exists in this relationship. That is, when inflation is below a certain level, Americans generally don’t search for it online. In the figure, that threshold appears to be around 4%. The black dots represent data points when inflation was below 4%, while the red dots capture values above that threshold through the first half of 2023. After that, a structural break emerges, illustrated by the blue dots.

What this pattern shows is that people are now searching for inflation more frequently at any given inflation rate than they were before 2020. Put differently, the public has become more sensitive to inflation news—and quicker to look it up on Google.

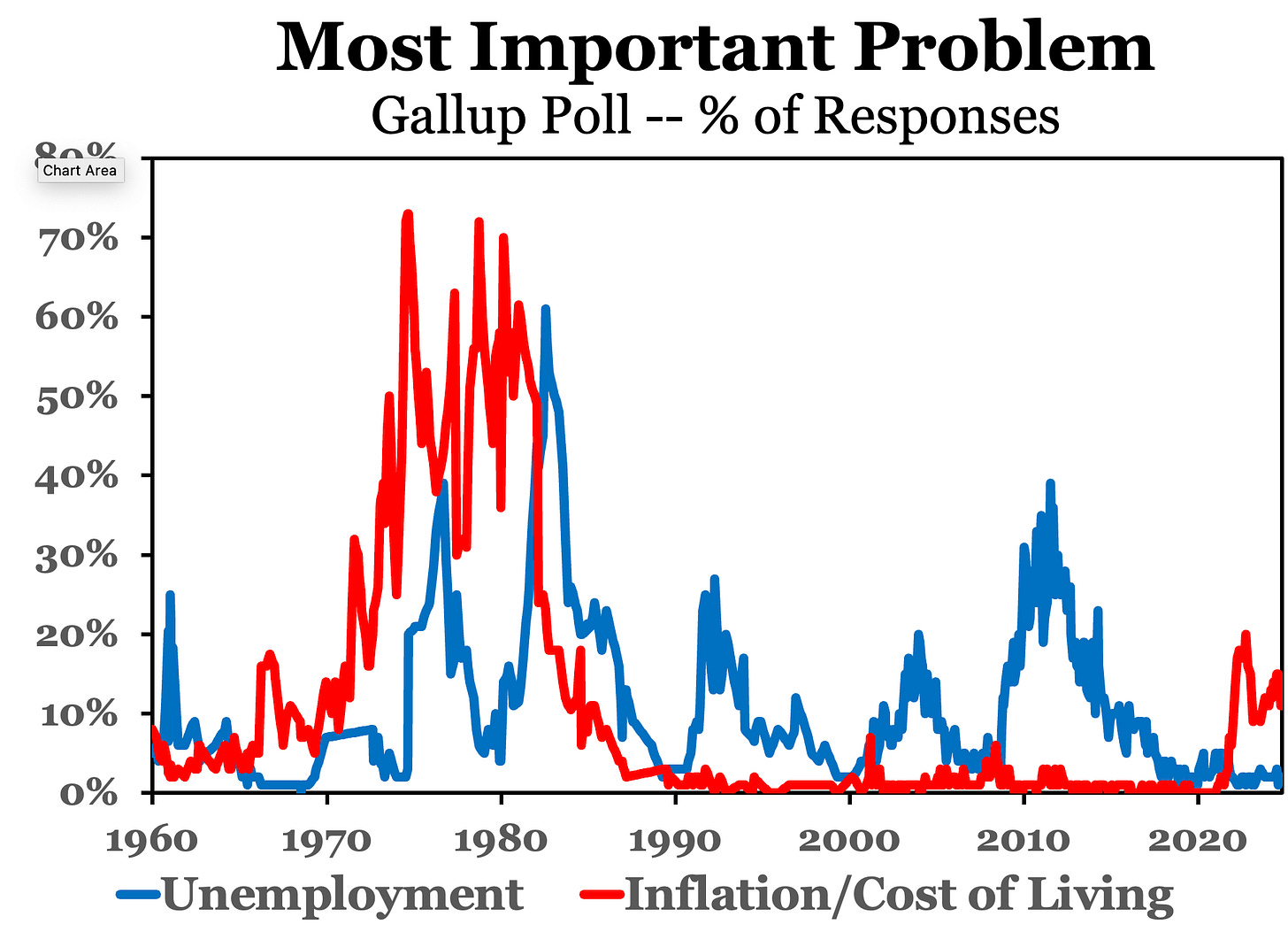

Next, we can find further evidence for inflation scarring in self-reported surveys. The figure below shows the inflation and unemployment responses for the Gallup Poll “Most Important Problem” going back to 1960. The concerns about inflation in the late 1970s and early 1980s are a sight to behold, but even in the more recent period the inflation worry—despite being smaller in absolute value—was the number one problem during the second half of 2022. More importantly, the figure shows it continues to be a persistent concern for Americans.

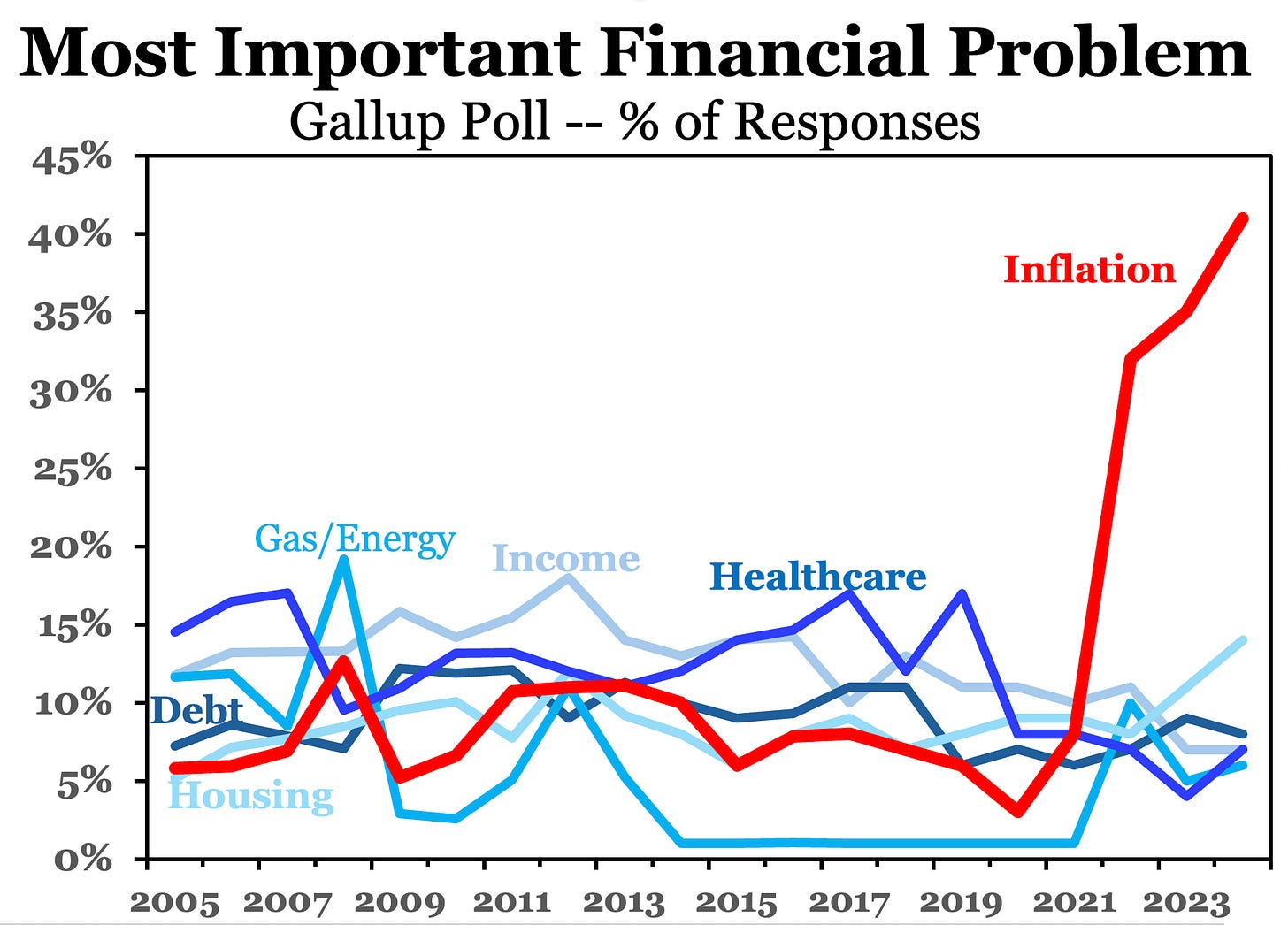

Gallup has another poll that comes out once a year and is more narrowly focused. It asks what is the “most important financial problem”? Inflation is by far the most important financial problem through 2024. Though our focus here is inflation concerns in the United States, it is worth noting that IPSOS has poll titled “What Worries the World” where it polls across 29 countries and also finds inflation to be an ongoing important concern. The inflation scarring is pervasive.

One final piece of evidence: consumer inflation expectations are more dispersed now than they were before 2020, signaling both greater uncertainty and increased sensitivity to price changes. This is reflected in the wider 25th–75th percentile spread shown below, indicating that even small inflation shocks can trigger strong reactions—especially among those already expecting higher inflation. Taken together, all of this suggests that inflation expectations are less firmly anchored than they once were.

Complicating the Return Journey to 2% Inflation

This inflation scarring complicates the Fed’s return journey to 2% inflation. Conventional wisdom says central banks should “look through” inflation caused by negative supply shocks as long as inflation expectations are well anchored. That is why the Fed was initially not worried about “transitory” inflation during the pandemic. It is also why Fed Chair Jay Powell is now invoking the “transitory inflation” claim about Trump’s tariffs, as they too can be seen as a form of a negative supply shock. Here is Chair Powell during the March 2025 FOMC press conference:

“As I've mentioned, it can be the case that it's appropriate sometimes to look through inflation if it's going to go away quickly without action by us, if it's transitory. And that can be the case in the case of tariff inflation. I think that would depend on the tariff inflation moving through fairly quickly and critically as well on inflation expectations being well anchored…

However, as outlined above, we are in a place now where one cannot assume inflation expectations are well anchored. As Nick Timiraos recently noted, a trade war that stokes inflation is far more challenging for the Fed now than it was during the 2018-2020 trade war because of this heightened inflation sensitivity. In short, the Fed’s 2025 playbook for trade wars cannot simply repeat what it used during the 2018-2020 period.

So What Can the Fed Do?

Pray the trade war ends. But in the absence of divine intervention in macroeconomic policy, there is something else the Fed could do: adopt a framework that allows it to better handle supply shocks while still maintaining a credible nominal anchor. Pat Horan and I have a paper where we make that case that is exactly what a nominal income target can do. The paper is titled A Two-for-One Deal: Targeting Nominal GDP to Create a Supply-Shock Robust Inflation Target. Here is an excerpt from the introduction:

In short, the 2021–2022 inflation surge, vividly demonstrated how challenging it is for central bankers to successfully look through temporary supply shocks. It requires monetary authorities to overcome a knowledge problem—identifying inflation caused by temporary supply shocks in real time—while keeping inflation expectations anchored. These daunting tasks led former Fed Vice Chair Lael Brainard to conclude that looking through temporary shocks “sounds relatively straightforward in theory [but is] challenging to assess and implement in practice” (Brainard, 2022).

This paper argues that there is a workaround solution to these challenges: nominal GDP (NGDP) targeting. It focuses central bankers’ attention on NGDP and allows them to look through short-term inflation movements. Nominal GDP level targeting (NGDPLT), where the central bank makes up for misses to the target, is especially attractive as it stabilizes aggregate demand and eliminates short-term swings in inflation caused by demand shocks, implying that any remaining shocks to inflation must be coming from supply shocks. NGDPLT, in other words, enables central bankers to see through short-term inflation movements caused by temporary supply shocks without having to identify the shocks.

NGDPLT also provides a credible nominal anchor since it stabilizes the nominal size of the economy and, therefore, keeps inflation expectations anchored. As a result, “a commitment to a nominal GDP level path is completely consistent with a commitment to a medium-term inflation target” (Woodford, 2013, p. 6). Central banks, therefore, that target the growth path of nominal GDP also are effectively targeting medium-run inflation. NGDPLT, consequently, is a “two-for-one” targeting deal that allows monetary authorities to successfully look through temporary supply shocks.

Conclusion

That brings us to the 2026 midterm elections. It would be ironic if inflation concerns—the very issue that helped elect Republicans in 2024—were to resurface due to tariff-driven price increases interacting with poorly anchored expectations, ultimately sparking voter unrest and costing the GOP at the ballot box. In this way, inflation could prove politically circular. Not only does the Fed need a nominal GDP level target—so do President Trump and the American psyche.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/feds/files/2021062pap.pdf

I couldn't agree more. We need NGDPLT in the US and here in the UK. All monetary regimes have flaws. A big advantage of NGDP targeting is its ability to deal with supply shocks, which inflation targeting fails to do (especially under a single mandate).

It shouldn't be too much of a jump for the Fed as they already explicitly take account of both inflation and real output (via employment), and have a 'make-up' element in their current AIT mandate/regime.

Its much tougher with the BoE. Responding to questions from reporters on my new IEA paper on NGDP targeting out this week, Treasury officials said they had no plans to change the Banks mandate from inflation targeting. A huge missed opportunity by the new Chancellor.