Pronatalism as Macroeconomic Policy

How Fertility and Digital Pronatalism Will Shape Economic Growth

As listeners of the podcast know, Macro Musings typically focuses on monetary policy, fiscal policy, and other business cycle phenomena. But macroeconomics is not just about short-run stabilization, it’s also about long-run economic growth. And a key driver of economic growth is population growth. That is why I have had guests like Jesús Fernández-Villaverde and Catherine Pakaluk on the show to explain demographic decline—fertility rates falling below replacement levels—and its implications for the economy. As seen below, demographic decline is affecting most of the world:

The connection between population and economic growth isn’t just about having more workers to produce goods and services—it's also about having more minds to generate the ideas that drive productivity and innovation. As Charles Jones articulated in a 2022 AER article, population growth is the ultimate constraint on the number of people searching for new ideas, which in turn constrains long-run growth. He highlights a simple but powerful causal chain: fewer people means fewer researchers, fewer entrepreneurs, and ultimately, fewer new ideas. And since ideas are the engine of productivity and prosperity, a shrinking population risks ushering in a future of stagnation—fewer breakthroughs, slower innovation, and diminished dynamism. All of this, as noted by Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, will have an adverse effect on social safety nets, inflation dynamics, public debt trajectories, and in the limit create an “existential economic crisis.” The demographic slowdown, in short, looms large as a major macroeconomic concern.

Yet one of the barriers to addressing this demographic challenge has been the widespread belief that pronatal policies simply don’t work. In this week’s episode, Lyman Stone pushes back on that consensus. He argues that France’s long-term investment in pronatalism has paid off, adding 5-10 million additional people over the past 80 years. Here is Lyman summarizing his findings:

The good news, then, is that pronatal policy may actually work! The bad news is that it requires small incremental gains over many, many decades. Can we bank on policymakers having this long of a horizon? Listen to the show to learn the answer and to glean other Lyman Stone insights.

Population and Economic Growth: A Closer Look

I want to step back and take a closer look at the relationship between population and economic growth. This connection operates through both the supply and demand sides of the economy. The idea generation story outlined above is primarily a supply-side story. There is also a demand-side story to the relationship that is equally important and first observed by Adam Smith in 1776. So let’s take a closer look at each story in turn.

Population Growth: the Supply-Side Story

As noted above, there is a supply-side story to the link between population growth and economic growth. The idea was formally developed by Nobel Laureate Paul Romer (1990) and became known as “endogenous growth theory.” It says more people means more potential inventors and ideas and, given knowledge is nonrivalrous, more technology and economic growth. Michael Kremer (1993), also a Nobel Laureate, provides empirical validation of endogenous growth over the very, very long run of human history. By showing that larger populations historically generated faster technological change—due to the sheer number of potential innovators—Kremer reinforces Romer’s core premise: more people mean more ideas.

There is a catch, however, to this supply-side story: diminishing returns. That is, while more researchers produce more innovation overall, they don't accelerate per capita economic growth as earlier models predicted. This was the finding of Charles Jones (1995) who used these findings to create “semi-endogenous growth theory.” Later work that he did with Bloom et al. (2020) confirms this trend: while research effort is rising exponentially, ideas per researcher are declining sharply. For example, maintaining Moore’s Law now takes more than 18 times the researchers it did in the 1970s. This evidence highlights that simply adding more researchers faces diminishing returns—each new researcher contributes less innovation than the previous one.

To be clear, this does not mean that demographic decline is any less harmful. Yes, we've already picked much of the low-hanging fruit of economic growth, and each additional piece of fruit is harder to reach. But with demographic decline, it's worse—we won't even have enough hands available to climb higher or plant new trees for future generations. Fewer people means fewer opportunities not just to harvest the tougher-to-reach fruits, but also to cultivate entirely new orchards of innovation.

Agentic AI as Digital Pronatalism?

Before we leave the supply-side story, I think it is important to address whether AI could play a role in offsetting the economic impact of demographic decline. I think it is possible given the advent of Agentic AI—AIs acting autonomously and proactively toward specific goals without human oversight—and that it might be useful to start thinking of AI policy as a form of digital pronatalism.

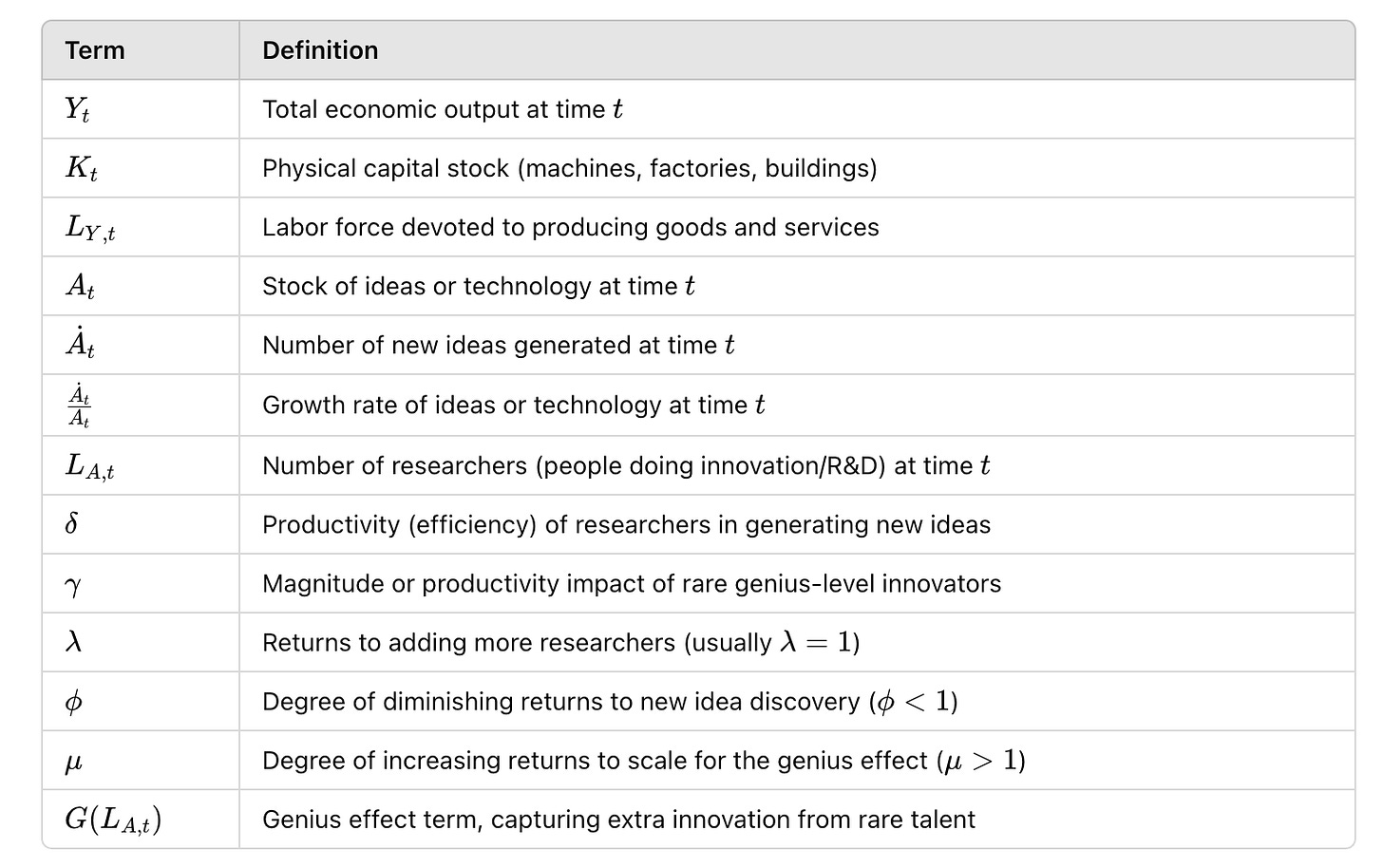

To see how, let’s revisit the Charles Jones (1995) semi-endogenous growth model. It recognizes that more researchers lead to more innovation, yet it also highlights diminishing returns as each new discovery becomes increasingly difficult. However, an intriguing plot twist exists: as the population grows larger, so does the likelihood of producing rare, transformative innovators like Einstein or Newton.

One can extend the Jones model to include this "genius effect” to show that beyond a certain scale, adding researchers doesn't just marginally boost innovation—it significantly increases the odds of groundbreaking discoveries. Thus, even as typical innovation faces diminishing returns, the rare but powerful breakthroughs from exceptional individuals can help offset these effects, providing occasional bursts of extraordinary economic progress. I had ChatGPT sketch out this extended version of the Jones model and posted it in the table below.

Now here is where Agentic AI (AAI) comes into the story. First, AAI could dramatically boosts the productivity and creativity of existing human researchers, pushing them to Einstein-like levels of breakthrough discoveries. Second, AAI itself could directly become an independent source of groundbreaking innovation itself, essentially serving as artificial "genius-level innovator."

AAI, in short, would increase the “genius effect” level through the existing supply of human researchers and through innovations created by AAI itself. This would reduce the urgency for standard pronatalist policies and complement them with digital pronatalism.

Digital pronatalism isn't just aspirational; recent empirical research provides evidence that AI is already making substantial contributions to innovation. Toner-Rodgers (2024), for example, demonstrates that breakthroughs in AI have significantly accelerated scientific discoveries and spurred new product development across various industries. Such evidence suggests that AAI will broaden the pool of innovators, reinforcing the notion that digital pronatalism may supplement traditional population-driven innovation.

The Jones (1995) Model with a Genius Effect

Population Growth: the Demand-Side Story

Innovation isn't driven by inventors alone—it also depends crucially on market size. As Adam Smith famously argued, "the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market." A larger population means more buyers, bigger potential profits, and stronger incentives to specialize and innovate, an idea further developed by economist Jacob Schmookler (1966). Empirical studies confirm this: Acemoglu and Linn (2004) found pharmaceutical innovation significantly increased when demographic shifts expanded market size.

Urban economists Edward Glaeser (Triumph of the City, 2011) and Enrico Moretti (The New Geography of Jobs, 2012) further highlight that densely populated cities amplify productivity by creating thicker markets, accelerating the adoption of innovations, and fueling a cycle of demand-driven economic growth. Thus, population growth doesn't just supply innovators—it actively pulls innovation forward by expanding market opportunities.

This is another reason for pronatalist policies: they increase the market size and demand-driven innovation. It is also why higher legal immigrations levels are so important to our future. Immigrants are adding more than just an extra supply of workers and extra demand for goods: they are spurring more specialization, innovation, and technology growth. Higher legal immigration is probably one of the easiest ways raise economic growth in America and strengthen it status in the world.

Conclusion

The link between population growth and economic dynamism, then, is multifaceted and powerful. On the supply side, more people mean more inventors, more ideas, and a higher chance of breakthrough innovations—especially if agentic AI emerges as a form of "digital pronatalism," amplifying human genius or becoming a source of genius-level innovation itself. On the demand side, larger populations mean bigger markets, deeper specialization, and stronger incentives for innovation. Together, these perspectives reinforce the urgency of addressing demographic decline through thoughtful pronatalist policies and higher legal immigration. In short, ensuring continued population growth—human, artificial, or ideally both—is critical not just for maintaining economic growth, but for preserving the dynamism, innovation, and prosperity that underpin our society’s long-run success.