Time is the Fire in Which We All Burn

One economist’s week of podcasts, papers, and policy fights

This week, I have been doing quite a bit of burning myself. Between preparing for the 500th episode of Macro Musings, releasing a new working paper, guesting on another podcast, and stepping into a debate where angels fear to tread, it has been a full—and fiery—week. So rather than offering my usual deep dive or policy riff, I thought I would take a step back and share what has been happening behind the scenes.

A Macro Musings Podcast Milestone

It is hard to believe, but next week’s show will be episode number 500 for the Macro Musings podcast. The first episode aired back on May 11, 2016 and the first guest was Scott Sumner. Not only was he the first guest, but he was my boss at the time and supported the podcast from the start. Since then, it has been an amazing ride. The podcast has allowed me to become part of important conversations on on monetary and fiscal policy, financial regulation, AI, demographics, and more. The podcast has also opened doors for me to write papers, attend conferences, and professionally grow in a manner that otherwise would not have happened. Finally, the podcast has also allowed me to meet interesting people and make new friends. People and relationships are what really matter in this life and the podcast has blessed me with so many new friends! Thanks to everyone—the guests, the audience, and my podcast team at Mercatus—for making it happen.

Given this special occasion, I am recording a video with a very special guest where we will reflect back over the past 500 episodes. If you have any questions about the show you would like me to answer, please put them in the comments below and I will attempt to answer them.

A New Working Paper on the Inflation Surge

My former colleague Pat Horan and I have released a new working paper this week that explores the causes of the 2021–2022 inflation surge. While much has already been written on this topic, many observers continue to attribute the inflation primarily to a series of exogenous shocks: shifts in consumer preferences, supply chain disruptions, and war-driven spikes in commodity prices. In this view, the surge in inflation was largely the result of unfortunate events outside the control of policymakers, with only a limited role assigned to fiscal and monetary policy.

However, a growing body of research challenges this narrative by emphasizing a crucial distinction: while preference, supply, and commodity price shocks can explain where in the economy inflationary pressures emerge, they cannot, on their own, account for the overall magnitude of inflation. For such sectoral disturbances to translate into broad-based, economy-wide inflation, they must be accompanied by macroeconomic policies—namely fiscal and monetary responses—that boost aggregate demand. In other words, without policy support during the pandemic, these shocks would likely have only shifted spending across sectors rather than increasing its overall level and igniting a general surge in inflation.

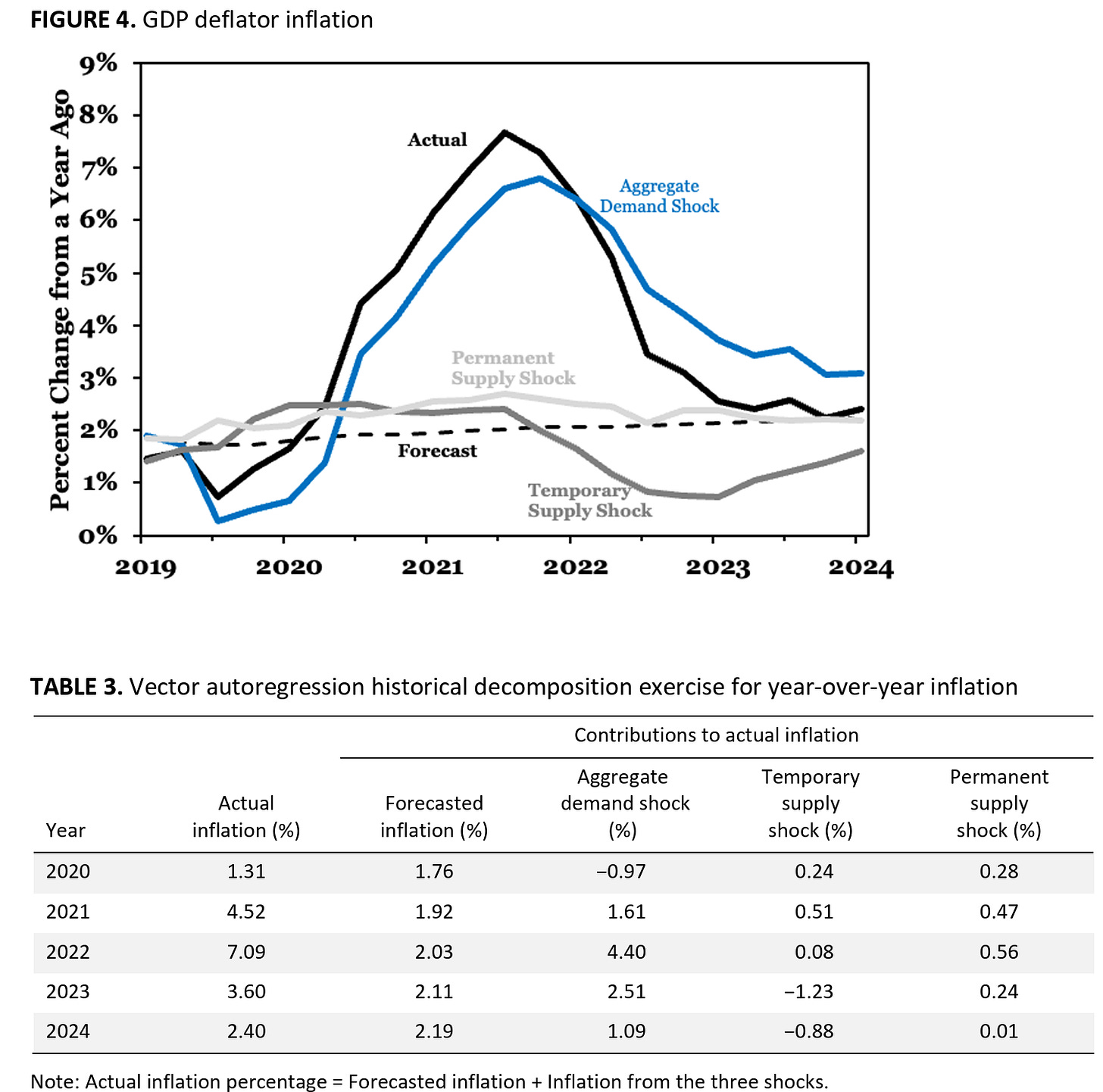

We document this debate in our paper and contribute to it by taking a standard New Keynesian model to identify an aggregate demand shock, a temporary supply shock, and permanent supply shock. We estimate these shocks in a structural vector autoregression and and are able to do a historical decomposition of GDP deflator inflation that is summarized in the figure and table below.

The big takeaway is that the inflation surge was largely the result of excess aggregated demand pressures. Check out the paper!

The Podcast Host Becomes the Guest

This week I also joined the Forward Guidance podcast to discuss many of the topics covered in this newsletter and on Macro Musings. Specifically, we chatted about the growing threat of fiscal dominance, the benefits and costs of the Fed’s ample reserve operating systems, why ending IOR would not save taxpayers money, the Fed’s framework review, and more. The host, Felix Jauvin, was great and it was a lot of fun to sit on the other side of the microphone! You can watch the show below.

Mend the Fed, Don’t End It

I recently waded into a ZeroHedge debate. As the old saying goes, “Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.” Count me among the fools. ZeroHedge is known for its hard money stance and fierce critiques of the Federal Reserve, so anyone defending the Fed in that space is essentially stepping into a field of rhetorical landmines.

That said, I came into the conversation with some preparation. I studied under George Selgin and Larry White, so I'm well acquainted with the free banking tradition and the historical arguments against central banking. Drawing on that background, I tried to offer a charitable and constructive case for preserving the Fed—using the free-market ideal not as a reason to abolish the central bank, but as a benchmark to improve it. The debate turned out to be surprisingly enjoyable and engaging.

Below is the video of the discussion, followed by a slightly edited version of my opening remarks.

Here are my opening remarks:

Thanks for inviting me to this debate. I'm really glad to be part of this conversation today, and it's a real pleasure to engage with Bob Murphy, a legend in the Austrian economics world. I've had the opportunity to debate Bob back in the glory days of macroeconomic blogging during and after the Great Recession.

In fact, if you look on Bob’s blog, Free Advice, you’ll find 49 posts between 2009 and 2016 where Bob engaged with and often debated me. Great memories.

In these posts, you’ll see Bob’s great sense of humor. In a May 2011 post, he noted that I was trained under George Selgin, influenced by Larry White, and knew my Ludwig von Mises. I had all the prerequisites to be a good Austrian monetary economist. And yet somehow — in Bob’s view — I had transformed from an angel of Austrian light into the dark force of a mainstream macroeconomist. I had become, in his words, the Count Dooku of Austrian economics.

Now, that analogy was brilliant and hilarious — but it also raises a bigger point. I, like Bob, come from a freedom-promoting tradition. I care deeply about liberty and human flourishing. In fact, I work at the Mercatus Center, a classical-liberal organization that promotes liberty — but in a pragmatic way.

So I approach the question of whether we should abolish the Fed as a kindred spirit to Bob, but one who believes that, since central banks are likely to be with us for the foreseeable future, the better path forward is to reform the Fed — to make it more consistent with a freedom-loving vision of the world.

To be clear, I’m very sympathetic to free-market monetary experiences. I draw inspiration from the Scottish free banking era (1716–1845) and the Canadian experience (1817–1935) — systems with no central bank, no deposit insurance, and competitive currency issuance. And yet, they delivered relative financial stability and growth. Bob is less enthusiastic about these cases and prefers a commodity standard like the gold stdandard with narrow banking. My view: whatever is your sound money ideal, use it to inform reforms to the Fed, not to abolish it.

So why do I take this pragmatic approach? I have three reasons.

First, the horse is out of the barn. Central banking is now the global norm as 192 countries have an independent central bank. These institutions are deeply entrenched. I’ve been openly critical of them including their roles in the Great Recession, the Eurozone Crisis, and pandemic inflation. But over time they only become more embedded, not less.

Two examples illustrate this.

First, during the Eurozone crisis, Greece suffered a 25% collapse in GDP and nearly 28% unemployment. Syriza came to power in 2015 campaigning to leave the euro and end austerity and yet they stayed. Why? Because the public feared hyperinflation and viewed the euro and the ECB as a shield. The crisis deepened Greece’s attachment to the euro and the ECB rather than breaking it.

Second, look at the global dollar system. Yes, the size of the U.S. economy matters, but so does the Fed’s role. By tolerating the eurodollar market, facilitating offshore repo, and operating global liquidity tools like swap lines and the FIMA repo facility, the Fed has helped entrench the dollar as the world’s monetary backbone. Today, total dollar credit to non-banks stands at $88 trillion more than double the euro’s. In short, the U.S. dollar network has become a global hegemon and it is the Fed who manages it.

These two examples illustrate why is highly unlikely major central banks, especially Fed, will ever be abolished. And, even were Bob able to abolish the Fed the likely global financial crisis that would follow would undermine his case for free-market money. One’s time is far better spent trying to work within this system to reform it.

My second point is we need to acknowledge that past free-market monetary systems didn’t endure. The Scottish free banking system was legislated out of existence in 1845 not because it failed, but because British Parliament wanted to centralize money creation.

The U.S. gold standard also had its challenges. It was largely an accident of history. The U.S. effectively got a gold standard in 1834 when Congress changed the U.S. mint ratio of silver to gold from 15:1 to 16:1. This overvalued gold and pushed silver out of circulation— a shift driven Andrew Jackson’s political battle against the Second Bank rather than by economic analysis. After the Civil War, silver was quietly demonetized in the Coinage Act of 1873 paving the way for a de facto gold standard by the time convertibility resumed in 1879. None of these changes reflected deep economic reasoning in favor of gold; rather, they were a series of ad hoc legislative choices and political pressures.

Moreover, the best version of the U.S. gold standard—the classical gold standard—that advocates often point to as an example lasted only 25 years, from 1879-1914. There never was a long golden age of a gold standard.

Then came the interwar gold standard (1925–1931), which quickly collapsed. Why? The main reason was the enfranchisement of the voters. Barry Eichengreen says it this way: “The interwar gold standard was doomed because it demanded political sacrifices that democratic governments — newly answerable to their electorates — could no longer make.” These same challenges would face any country attempting to return a commodity standard today.

My third and final point is this: the real issue isn’t central banking itself — it’s society’s underlying commitment to price stability and, even more fundamentally, to fiscal responsibility. If you look at the long-run U.S. price level up through World War I, you’ll see that it rose and fell over time, but on average it was remarkably flat, essentially a straight line. That kind of stability persisted despite major disruptions: the suspension of the gold standard from 1861 to 1879, the early experiments with two different central banks, and the issuance of large amounts of fiat money during the Civil War.

There will always be wars, pandemics, and national emergencies that often are financed by an inflation tax. But historically, the damage was contained because societies understood that these were exceptions, not norms. As Robert Barro’s “tax smoothing” model suggests, governments have often unwound wartime inflation by restoring monetary and fiscal discipline in peacetime. Our efforts, then, should not just be about reforming the Fed but restoring fiscal stability to U.S. government finances.

So, to summarize my reasons for not abolishing the Fed, but reforming it are:

1. Central banks are deeply entrenched and not going anywhere.

2. Historical free-market systems didn’t last — and not because they failed economically, but because they weren’t politically robust.

3. The real issue isn’t who issues the money — it’s whether we as a society are committed to fiscal discipline.

We need to mend the Fed, not end it. And we need to get our fiscal house in order.

PS - at the very least, if the Fed wants to pay IOR above market rates, it should offer accounts to the general public.

It bothers me when, at various times, the rate paid on IOR exceeds the 1-month t-bill, and often also the 3-month and even 6-month t-bill. This even when the curve on Ts has been upward sloping. At those times (the majority of the last 17 years), how can the payment of IOR not cost more than if there were no IOR?