From "Liberation Day" to Stagflation's Return?

Why Trump’s Tariffs, Inflation Scars, and a Politicized Fed Could Recreate the 1970s

President Trump made good on his promises this week with a sweeping announcement of new tariffs—what he’s calling “Liberation Day.” Nearly all imports will now face a 10% universal tariff, with even steeper “reciprocal” tariffs for countries like China (34%), Vietnam (46%), and the EU (20%). Financial markets judged these tariffs harshly—stocks tanked, bond yields fell, the dollar tumbled, oil prices fell, and copper prices dropped—and in a manner that suggests they see a recession ahead.

Markets are reacting negatively because the tariffs are effectively a large tax increase on Americans implemented without Congressional approval, a disruption to global supply chains that support U.S. manufacturing, a drag on U.S. investment spending, and—should Trump change his mind—a source of additional policy uncertainty. And that is even before considering the retaliatory measures foreigners will likely impose on us and the abandonment of allies we need in our contest with China. There is no sugarcoating the pain of these new tariffs.

Unfortunately, these developments may be just the beginning. Should President Trump persist in implementing the new tariffs, the conditions would be ripe for the return of stagflation—rising prices alongside slowing growth—given the lingering inflation scars from the pandemic, the prospect of a politicized Fed, and the outlook for large, persistent government budget deficits. To understand what might lie ahead, it’s worth revisiting the classic case of stagflation in the 1970s.

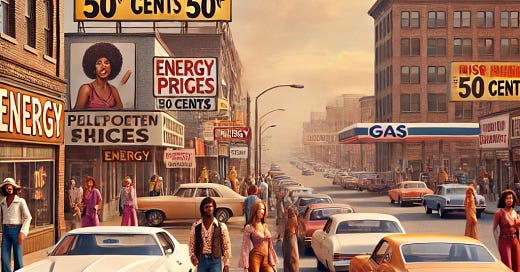

That 1970s Show

The 1970s stagflation story first begins with the supply side of the U.S. economy. Productivity growth, which had been strong in the postwar era, began to slow markedly, reducing the economy’s capacity to grow without generating inflation. At the same time, two major oil shocks—in 1973–74 and again in 1979—sent energy prices soaring. These shocks, driven first by the Arab oil embargo and later by the Iranian Revolution, sharply raised production costs across the economy and squeezed household budgets.

But these developments were only part of the story. In an influential paper, Robert Barsky and Lutz Kilian (2001) showed that the Great Stagflation of the 1970s wasn't just about the oil shocks. The real driver, in their view, was an overly expansionary monetary policy that accommodated rising prices rather than resisting them. In other words, the Fed wasn't just reacting to oil shocks—it was validating them by letting inflation expectations drift upward. This policy stance, they concluded, provided a far more compelling explanation for the era’s stagnation than global commodity prices alone.

Andrew Levin and John Taylor echo this view, documenting a pattern of “stop-start” monetary policy from 1965 to 1980. The Fed repeatedly hesitated to act against inflation, then tightened too late and too briefly—only to ease again. Their conclusion? The Fed “fell behind the curve,” fueling persistent inflation without sustained growth.

But the 1970s stagflation story is not just one of economic misjudgment—it’s also a story of political influence. As Thomas Drechsel (2024) documents, the Fed during this period operated under intense political pressure, especially from Presidents Lyndon B. Johnson and Richard Nixon. Arthur Burns, Nixon’s appointee and close confidant, was pressured to keep monetary policy loose heading into the 1972 election. This political interference weakened the Fed’s willingness to counter inflation, even as price pressures mounted. Drechsel's research reinforces the Barsky-Kilian view by showing that visible political meddling had a uniquely persistent inflationary effect—stronger than typical monetary easing alone. In short, the politicization of monetary policy didn’t just dull the Fed’s tools; it eroded its credibility and fueled the very stagflation it was meant to prevent.

Taken together, these accounts reveal a central bank that—under political pressure and lacking resolve—consistently fell short in responding to inflationary shocks. By accommodating rather than resisting these pressures, the Fed helped turn supply disruptions into a prolonged era of stagflation. It’s a cautionary tale with renewed relevance for today.

The Conditions are Now Ripe for Stagflation’s Return

This brings us to the present—and the growing risk that history could rhyme. A number of developments, if left unchecked, could push the U.S. economy back toward a world of stagflation.

First, there are the Trump tariffs. They are large in magnitude and represent a negative supply shock to the economy. Throw in retaliatory measures and further disruptions to global supply chains caused by the trade war and we have our equivalent to the negative supply shocks of the 1970s.

Second, we have the lingering inflation scars from the pandemic. As I argued in Once Bitten, Twice Shy, households today are far more sensitive to inflation threats and quicker to adjust their behavior than they were before 2020, having lived through the inflation surge of 2021–2022. Consumer inflation expectations now resemble a dry tinder pile—and Trump’s tariff shock may be the match that sets it ablaze. Early signs suggest the fire may already be catching.

Third, there are the growing threats to the Fed’s independence. As the trade war slows the economy, political pressure to cut interest rates will likely intensify—and it may not stay behind closed doors. Trump has a history of publicly criticizing the Fed and could again push for easier policy to blunt the economic fallout of his own trade agenda. What’s new this time is the legal context. His recent removal of two FTC commissioners—despite statutory protections—signals a broader challenge to the autonomy of independent agencies. If courts uphold this move and weaken the Humphrey’s Executor precedent, the Fed’s independence could be next. A future Trump administration might seek a more compliant Fed chair and attempt to remove governors who resist his agenda. Such an erosion of institutional independence would undermine the Fed’s inflation-fighting credibility—and, in doing so, echo one of the most damaging dynamics of the 1970s.

Finally, the prospect of persistent budget deficits, as projected by the CBO, raises the risk of fiscal dominance—where monetary policy is effectively subordinated to the needs of the Treasury. In such a scenario, the Fed may face pressure to keep interest rates low not to stabilize inflation, but to manage the government’s growing debt burden. That, too, would weaken the Fed’s inflation-fighting resolve and further fuel the kind of policy accommodation that helped entrench stagflation in the 1970s.

Taken together, these developments suggest that a repeat of 1970s-style inflation is not far-fetched. A large negative supply shock, inflation-sensitive households, mounting political pressure on the Fed, and the looming threat of fiscal dominance all echo the conditions that gave rise to stagflation half a century ago. While history never repeats itself exactly, the parallels are close enough to warrant serious concern—and to demand a policy response from Congress that avoids the mistakes of the past.

But what about bond markets?

Now, there’s one big problem with my “return of stagflation” story: the Treasury bond market isn’t buying it. Yields suggest that investors expect only a modest inflation bump from the tariffs this year, followed by a return to disinflation. In other words, markets are pricing in a standard recession—not stagflation.

It’s always risky to second-guess the wisdom of markets. But allow me to make the case. It may simply be that the Treasury market lacks the “muscle memory” to recognize a stagflationary environment. After decades of disinflationary shocks and inflation largely under control, markets might be defaulting to the old playbook. A true 1970s-style mix of rising prices and stagnant growth may fall outside their lived experience—and their models. Yes, I may live to regret these words—but the market’s confidence could prove to be misplaced.

Conclusion

Of course, my stagflation scenario hinges on one key assumption: that President Trump follows through on the tariffs and sticks with them. That path is not inevitable. Market turmoil and public frustration over rising prices could force a reversal. A sharp political backlash—whether through midterm election losses or mounting pressure from business groups—might lead to a retreat. Congress, too, could play a more assertive role in challenging the tariffs or reasserting its trade authority. In short, the stagflation cycle doesn’t have to run its full course. But if these counterweights fail to materialize, or come too late, the echoes of the 1970s could grow louder—and harder to ignore.

Maybe not stagflation

https://marcusnunes.substack.com/p/trump-is-afraid

Sorry. Not buying any of it. You have completely ignored the 1970s regulatory structure which included, among other things, price controls on oil. It was, of all people, Jimmy Carter who finally removed price controls on oil thereby ending gasoline shortages. Carter was followed by Reagan who began the deregulation of highly regulated industries such as banking, telecommunications, and airlines. The U.S. economy took off in the 1980s.

In Trump's second term he is embarking on another round of cutting regulations that hamper productivity, and he is again attracting investment in the U.S. During his first term Trump's tax policy encouraged repatriation of dollars held overseas by U.S. companies. This time his message is to multinational companies is to "build it here" to avoid tariffs, and companies have responded by promises of large investments in the U.S. There will be no stagflation under Trump.