One of my favorite recurring topics on the podcast—and in my writing—is the plumbing of central bank operations. While it may not be everyone’s idea of excitement, the Fed’s operating system has long fascinated me and I have been fortunate to discuss it with leading voices like Bill Nelson, Lorie Logan, Claudio Borio, Ulrich Bindseil, Peter Stella, Loretta Mester, Sam Schulhofer-Wohl, Roberto Perli, Brian Sacks , Isabel Schnabel and George Selgin. I even had the opportunity to moderate a panel on the subject at the 2025 Atlanta Federal Reserve Financial Markets conference. This is, as they say, my cup of tea.

Given how technical and niche this topic is, I have always assumed these conversations would stay confined to a relatively small circle of monetary policy enthusiasts. So you can imagine my surprise when Senator Ted Cruz recently thrust the Fed’s operating system into the national spotlight. In a bold move, he called on Congress to repeal the Fed’s authority to pay interest on reserve balances (IORB), claiming it would save taxpayers roughly $1 trillion over the next decade by halting interest payments to banks. He also suggested it would help stem the Fed’s mounting balance sheet losses. Suddenly, what had long been an esoteric subject for Fed watchers was now front-page fiscal politics.

Senator Cruz’s proposal received “robust discussions” among his Senate colleagues and even President Trump also got to hear the case for ending IORB, according to Bloomberg:

“I made the case directly to the president in the Oval Office last week, I made the case at lunch today,” Cruz said in an interview at the Capitol. If the idea is added to Trump’s massive tax and spending package, it could help to offset the cost and limit its impact on the deficit, Cruz said.

Senator Cruz also made the case for his proposal on CNBC:

I never thought I would see the day when the Fed’s operating system became mainstream conversation. Thanks, Senator Cruz, for making it happen.

Senator Cruz’s proposal is already facing some pushback. Some of the criticism is fair, but much of it overlooks deeper, longstanding concerns about the Fed’s current operating framework that is known as the ‘floor’ or ample reserves system. To his credit, Senator Cruz has created an opening to revisit these issues, and that is exactly what I plan to do in this post. First, I will assess how much taxpayer savings his proposal might actually yield. It turns out to be modest at best. However, I will argue that the real costs of the floor system go well beyond the dollar amount of Fed remittances to the Treasury. These structural costs, in fact, strengthen the case for reform. I will then make the case that Senator Cruz should advocate for a shift from a floor system to a ceiling system. Finally, I will lay out the steps needed to make such a transition a smooth one.

The Cost-Saving Story is Complicated

Senator Cruz’s proposal would end IORB. But would it also end payments to the banking industry from the federal government? Not really. For a given level of liquidity demand, banks would simply shift from holding reserve balances to holding Treasury bills (T-bills) if reserves no longer earned interest. The payments from the federal government to banks would continue, just in the form of interest on T-bills rather than interest on reserves.

In that sense, eliminating IORB would be largely a wash in terms of federal payments to the banking system—unless the IORB rate has been systematically higher than T-bill yields. Only when the Fed pays banks more on reserves than they could earn holding comparable risk-free assets like T-bills can one view it as a taxpayer-funded subsidy.

So have banks been earning more on IORB? The figure below plots the spread between the IORB rate and the 1-month T-bill yield. It reveals that over the 2008–2024 period, IORB rates did slightly exceed T-bill yields—by about 20 basis points on average—suggesting a modest cost to taxpayers.

The table below converts this spread into dollar terms. In the first column, the table reports the actual interest payment to depository institutions each year as reported in the Federal Reserve’s annual financial statements. The third column reports how much of the IORB payment—the subsidy—was due to the IORB-T-Bill spread.

The table shows that from 2008 to 2024, total IORB payments amounted to nearly $394 billion, but only about $55 billion—around 14 percent—reflected payments above what banks could have earned on Treasury bills. In all years, the subsidy was less than 1 percent of GDP. This suggests that while IORB payments appear large in dollar terms, the actual economic subsidy to banks has been relatively small. All of this means that ending IORB would produce only modest savings over the next decade. It would be something, but nowhere near a trillion dollars of savings.

This modest savings, though, is not the end of the story for taxpayers. Eliminating IORB would likely reduce the net income generated by the Fed’s balance sheet and therefore shrink the remittances the Fed returns to the U.S. Treasury. Under the floor system, the Fed’s balance sheet functions much like a fixed-income hedge fund—borrowing short via bank reserves and ON-RRPs and investing long in Treasury securities and agency MBS through the System Open Market Account (SOMA).

Up until 2022, this maturity transformation produced substantial net income, far exceeding what the Fed would have earned under a smaller, scarce-reserve system. This can be seen by comparing actual SOMA earnings and remittances to a counterfactual path for them based on their average levels during 2005–2008, the period when the Fed operated under the old corridor system. Even with the recent operating losses, the Fed projects that SOMA earnings will recover and more than offset those losses over time. From 2009 through 2034, the Fed expects the SOMA portfolio to generate $1.885 trillion in net income under the floor system—nearly $1 trillion more than the counterfactual $923 billion it would have earned under the previous scarce reserve regime.

In short, any potential savings from eliminating the IORB–T-bill spread would likely be more than offset by a decline in SOMA net income over the longrun. Rather than delivering a windfall to taxpayers, ending IORB could reduce Treasury remittances and leave the public worse off, not better.

Senator Cruz’s proposal, in other words, would not deliver the kind of taxpayer savings that have been advertised. But that does not mean the ample reserve system is without cost. The real cost of the floor system is that it displaces private participants across a wide range of funding and liquidity markets. Put differently, it expands the Fed’s footprint in the financial system while shrinking the space for private-sector discipline, innovation, and price discovery. These institutional and structural distortions are very consequential.

The Real Costs of the Floor System

Consider the aforementioned point that the Fed has effectively become the world’s largest fixed-income hedge fund, managing a multi-trillion-dollar portfolio of long-term securities funded by overnight borrowing. In doing so, it has displaced private intermediaries like PIMCO and reshaped how maturity transformation occurs in the financial system. Unlike private asset managers, however, the Fed is highly leveraged and shielded from market discipline. Its funding is guaranteed, and its losses are quietly absorbed through deferred remittances to the Treasury. Yes, this hedge fund–like posture has produced larger remittances to the Treasury, but is that the proper role of a central bank? If there are alternative ways for the Fed to satiate liquidity demand and maintain interest rate control—and there are as noted below—the answer should be an emphatic no.

Or consider the hollowing out of the overnight unsecured interbank market—the federal funds market—since the Fed adopted a floor system. With banks flush with reserves and able to earn interest risk-free at the Fed, they no longer need to borrow from each other. What remains is mostly regulatory arbitrage between FHLBs and foreign banks, stripping the market of its former role in price discovery and counterparty discipline. The result is effectively a missing market.

Relatedly, with remunerated reserves readily available, banks have less incentive to manage liquidity using market tools like repos, commercial paper, or contingent credit lines. They also have less need to use Fed’s Discount Window and daylight overdrafts, further stigmatizing their use and leaving banks less able to engage with emergency facilities during times of stress.

The floor system has also made the Fed, at times, the largest counterparty in the repo market for non-bank institutions such as money market funds. Through the ON-RRP facility, these firms park trillions of dollars at the Fed rather than lending in private repo markets. Supporters rightly note that the facility helps the Fed maintain control over short-term interest rates in a system flooded with reserves. But that is precisely the problem: to maintain interest rate control, the Fed had to insert itself as the central counterparty in the overnight funding market. This is not a side effect of the floor system but a defining feature.

In short, the floor system has weakened the muscle memory of markets and financial firms. With the Fed supplying ample reserves, institutions no longer practice—or even need—the tools they once used to manage liquidity dynamically. Over time, this fosters a brittle financial ecosystem that, paradoxically, demands even more Fed intervention during periods of stress, further entrenching the central bank’s role. This is not to say the Fed’s balance sheet should never be used, it clearly should in a crisis. But when the crisis passes, those interventions should be quickly and deliberately reversed to avoid long-term distortions. Instead, we see the ratcheting effect on the Fed’s balance sheet described by Bill Nelson (2024) and Acharya, Chauhan, Rajan, and Steffen (2023) and no serious effort to move away from the floor system.

Senator Cruz’s call to end interest on reserves may not generate a fiscal windfall, but it raises the right question: why has the Fed become so central to the financial system? If the real costs of the floor system are market displacement and growing dependence on the central bank, then it is worth considering alternative operating systems for the Fed.

A Ted Cruz Moonshot: Move the Fed to a Demand-Driven Ceiling System

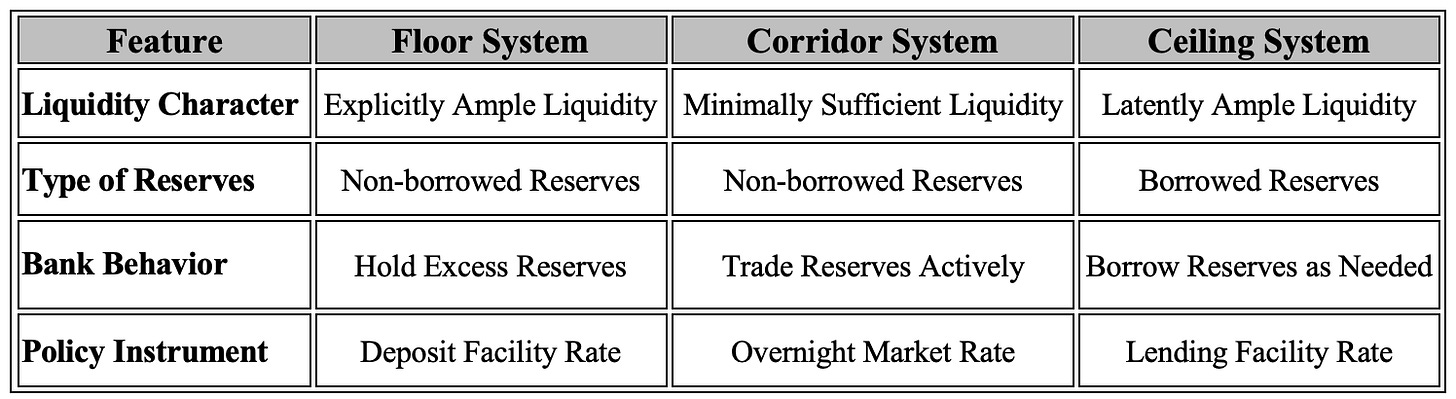

Senator Cruz proposal would end IORB and presumably take us to a corridor operating system. The Fed, however, could follow the lead of other central banks and instead move toward a demand-driven ceiling system. In this setup, banks are not preloaded with reserves, but can access all the liquidity they need through the Fed’s standing lending facilities—the Discount Window and the Standing Repo Facility—at the policy rate. This approach avoids flooding the system with reserves while still satisfying liquidity demand since reserves are available on demand. Put differently, liquidity is latently ample in the ceiling system versus being explicitly ample in a floor system.

A demand-driven ceiling system also satisfies the Friedman rule by ensuring banks are effectively satiated with liquidity through frictionless access to reserves at the central bank’s lending facilities. With overnight market rates anchored to the lending facilities rate, banks face no meaningful opportunity cost when deciding whether to hold reserves or access liquidity as needed. And because reserve balances are minimal in a ceiling system, there is no meaningful sense in which banks are being taxed by IORB being below the overnight market rate. This framework avoids the distortions of a large Fed balance sheet in the floor system and the under-remuneration risks of the corridor system. Notably, central banks such as the ECB, Bank of England, RBA, and Bank of Canada are already moving in this direction, as I discussed in a previous post.

To be clear, moving to a ceiling system would be a major shift for the Fed. So, what would it take for Senator Cruz to turn this moonshot into reality? The three biggest hurdles I see to making it happen are downsizing the Fed’s balance sheet, dealing with the large and volatile Treasury General Account (TGA), and making the Discount Window (DW) and Standing Repo Facility (SRF) a regular, accepted part of day-to-day liquidity management. Here are three steps that could help the Fed clear these hurdles.

Step 1 - Do a Treasury-Fed Asset Swap

Whether Senator Cruz sticks with his original proposal to eliminate IORB or pivots to the more ambitious goal of shifting the Fed to a demand-driven ceiling system—which would retain IORB but set it below overnight market rates—banks would naturally seek to minimize their reserve holdings, as reserves would yield less than Treasury bills. To maintain control over interest rates in this environment, the Fed would need to adopt some combination of (1) selling off its Treasury securities, (2) expanding term and overnight reverse repo operations, and (3) reinstating reserve requirements. Of these, selling off its assets would be the most important—and potentially the most disruptive—step in moving away from a floor system. So how could shrinking the Fed’s balance sheet be done smoothly?

Peter Stella has offered an elegant two-step solution. First, the U.S. Treasury would issue additional short-term T-bills and swap them for the longterm Treasury bonds currently held by the Fed. Since these new T-bills would not fund budget deficits, they would not count against the debt ceiling. Second, once the Fed holds the new T-bills, it could gradually sell them into the market, exchanging reserves for T-bills in a way that drains excess liquidity without dumping longterm Treasuries into the market and triggering financial instability. Drawing on his experience at the IMF advising central banks in similar situations, Peter aptly calls this approach “exiting well.”

As an added bonus, this Treasury–Fed asset swap would also eliminate the Fed’s current balance sheet losses, since the duration of its assets would now match that of its liabilities.

Step 2 - Bring Repo Operations to the TGA

Now, even if the Fed dramatically reduced its asset holdings, it could still experience large swings in its balance sheet due to the volatility of the Treasury General Account (TGA). The TGA acts as the government’s checking account at the Fed and when its balance rises or falls sharply—say, due to tax payments or large Treasury auctions—it causes equally sharp fluctuations in the reserve balances of the banking system. These swings would disrupt short-term interest rate control in a corridor or ceiling framework unless the Fed maintains a large buffer of reserves. Fortunately, there is a solution here too.

One promising approach, proposed by Bill Nelson, is to neutralize TGA volatility with daily repo operations. When Treasury activity drains reserves—say, by pulling in $100 billion through tax collections—the Fed would simultaneously inject an equal amount back into the banking system via overnight repos. Conversely, when Treasury spending pushes reserves into the system, the Fed could allow repo positions to roll off. This kind of daily offsetting restores the active reserve management that characterized the pre-2008 corridor era, but would allow for a leaner corridor or demand-driven ceiling system. It would also reduce the need for a bloated balance sheet simply to accommodate fiscal volatility, helping the Fed maintain rate control without crowding out private market activity or expanding its footprint unnecessarily.

Step 3 - Turn the Discount Window and Standing Repo Facility Routine into Routine and Reliable Liquidity Tools

A final challenge to making a ceiling system work in the United States is that the Fed’s lending facilities—the Discount Window (DW) and the Standing Repo Facility (SRF)—are not widely used due to stigma and institutional design choices. Banks fear that borrowing from the DW will signal financial weakness to regulators, counterparties, or the public. Meanwhile, the SRF is relatively new and limited to primary dealers and eligible depository institutions. This narrow counterparty list is unfortunate given the importance of non-bank financial firms like money market funds, insurance companies, and hedge funds in distributing liquidity to the U.S. financial system. To make a ceiling system work in the United States requires reforming these facilities.

Here are some suggestions for the DW. First, following Susan McLaughlin’s recommendation, the Fed should restructure the DW into two distinct tools: one for routine, on-demand liquidity for healthy banks, and a separate facility for recovery or resolution funding—eliminating the ambiguous and stigmatized primary/secondary credit framework. Second, the Fed should adopt Bill Nelson’s proposal for a modernized version of the Term Auction Facility (TAF)—regular auctions of term credit that normalize DW usage and reduce stigma through transparency and competitive pricing. Third, the Fed and banking regulators should allow pre-positioned DW collateral to count toward liquidity regulations like the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), recognizing it as a legitimate and reliable funding source. In parallel, the Fed could introduce a Committed Liquidity Facility (CLF)—a pre-approved, collateralized credit line that banks pay a fee for and can draw upon as needed, giving them a dependable form of liquidity insurance that can also be recognized in regulatory stress testing. As for the Standing Repo Facility (SRF), its effectiveness could be greatly enhanced by expanding access to non-bank financial institutions through centrally clearing, as proposed by Darrell Duffie. These changes would help integrate both the DW and SRF into day-to-day liquidity management, rather than treating them as tools of last resort.

Conclusion

Senator Cruz’s proposal may not yield the headline fiscal savings he hoped for, but it has opened the door to a much-needed debate about the future of the Fed’s operating system. The floor, or ample reserve, system has evolved into an expansive framework that distorts money markets, entrenches the Fed as the central counterparty, and requires a permanently large balance sheet to function. A demand-driven ceiling system offers a cleaner alternative: liquidity on demand without the excess, market discipline without fragility, and monetary control without fiscal sprawl. Getting there will not be easy. It will require Treasury-Fed coordination, active reserve management, and a cultural reset around the Fed’s lending facilities. But the payoff would be enormous: a leaner, more resilient, and more accountable central bank. That’s a moonshot worth aiming for.

Update: my original calculation of the extra payment or subsidy going to the banks was incorrect in the table. Thanks to a reader for pointing it out to me. I have now corrected the mistake and made some minor text change to reflect the update.

Well done Milton Friedman‘s original proposal was to pay interest on required reserves, but not on excess reserves

I have some confusion about what is called “ample reserves” since according to papers and articles from the NY Fed the “ample-reserves regime” is placed in the middle of the “scarce-reserve regime” and the “abundant-reserve regime” so it seems closer to a corridor system than to a ceiling system. Where can I find information where these concepts are clarified or defined?