Winners, Losers, and the Lingering Fears of Inflation

Why Inflation is More than a Macroeconomic Phenomenon

This week on Macro Musings, I spoke with Mark Blyth about his new book Inflation: A Guide for Losers and Users. Coauthored with Nicolò Fraccaroli, the book offers a rich political economy view of inflation: what it is, who it helps, who it hurts, and why it is far more than just a technical macroeconomic phenomenon. Mark lays out five things they do not tell you about inflation that should reshape how we think about it. These include that there are different types of inflation, that inflation indexes are deeply political constructions, and what gets measured as inflation affects how it is perceived and who bears the costs.

In our conversation, we used those five points as a jumping-off ground to unpack broader questions about inflation theory and policy. We revisited the old Milton Friedman dictum—inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon—and asked whether it still holds up in today’s global, supply-shock-ridden economy. We explored competing macroeconomic theories used to explain the 2021–2022 inflation surge: New Keynesian models with their expectations-driven Phillips curves, the Fiscal Theory of the Price Level (FTPL), Monetarism, Hydraulic Keynesianism, and what might be called the Bottleneck Theory of Inflation where institutional frictions and sectoral constraints drive price pressures. My own view, as I note in the podcast, is that excessive aggregate demand pressures, fueled by macroeconomic policy, was the primary driver of the inflation surge. I outline this view in forthcoming paper, so stay tuned for it.

We also discussed what brought inflation back down and why the “soft landing” caught many observers by surprise. A final theme Mark and I explored was the psychological scarring left by the recent inflation surge and why policymakers would be wise not to overlook it. While inflation has cooled, its imprint on household behavior and expectations still lingers. I will say more on this in the remainder of the post, but before doing so here is some bonus content from the podcast recording that highlights Mark’s other talents.

Once Bitten, Still Twice Shy?

As noted above, one theme we discussed was the lasting psychological impact of the recent inflation surge. Even with inflation well off its peak, households remain unusually sensitive to new price shocks, a point I emphasized earlier this year in a post titled Once Bitten, Twice Shy. In that piece, I documented how inflation expectations have become more fragile and I argued that this heightened sensitivity complicates the Fed’s job. Specifically, the traditional central bank playbook of “looking through” temporary supply shocks becomes much harder to do when inflation expectations are no longer firmly anchored. I suggested that this could pose real challenges for the Fed, particularly if Trump’s trade war introduced a new wave of price shocks.

Now that it has been nearly three months since that post, how has my thesis held up? So far, price shocks from the trade war have not materialized in a meaningful way, but they are likely to emerge later this year. On that point, I will give myself a passing grade for “work in progress.” As for the broader claim that household inflation expectations remain fragile, the data continues to support it, though with some signs of modest improvement. Let’s take a look at the updated evidence.

Survey Evidence

The first piece of evidence is the survey-based, one-year ahead measure of consumer inflation expectations. The figure below reports versions of this measure from the New York Fed, the Conference Board, and the University of Michigan. All of them revealed a significant surge from January through April of this year. In May, these measures started to decline, but still remain elevated.

Not only are inflation expectations elevated in these surveys, the uncertainty surrounding them are meaningfully larger than during the pre-pandemic period. For example, the figure below shows that the average 25th-75th percentile spread in the New York Fed’s measure has grown almost 200 basis points. This widening of the spread implies that nominal anchoring around the inflation target has weakened.

Gallup similarly shows in its “Most Important Problem” poll that inflation continues be an important concern for Americans, even as it has come down from its high in late 2022. It not only remains elevated, but remains far more important than the unemployment concern.

Another Gallup poll that more narrowly focuses on the “Most Important Financial Problem” and is reported once a year shows inflation to still be the top financial problem. It too has come down some over the last year.

All of these self-reported measures indicate that the pandemic inflation surge permanently raised the public’s concern about inflation in the United States. This inflation scarring is also apparent abroad. The June 2025 IPSOS poll titled “What Worries the World” draws from a sample of 29 countries and similarly finds inflation to be an ongoing and important concern across the world. The inflation concern has come down from its high, but remains one of the two top worries in these countries.

Revealed Preference Evidence

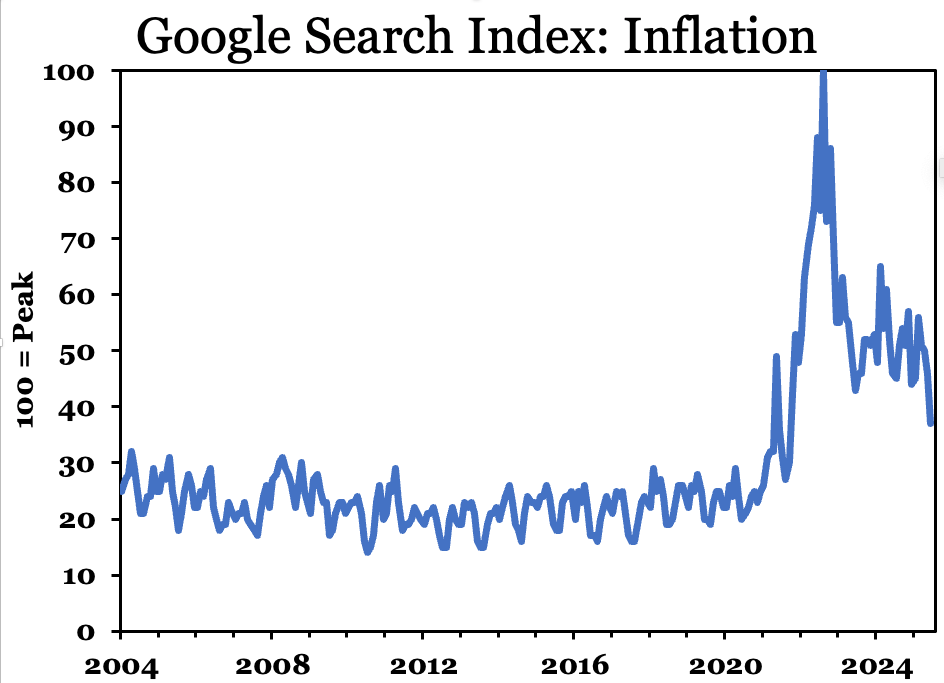

Survey and polling data are useful, but they have limits because they are self-reported. People may say they are worried about inflation, but not necessarily act on those concerns. That is why it is helpful to examine revealed preference data, which reflects how people behave rather than what they say. One such indicator is Google search activity. Using the Google Trends tool, we can see that public interest in “inflation” has remained consistently higher than it was before the pandemic. While search volumes have declined from their peak, they remain well above pre-2020 levels and suggest that inflation remains top of mind for many households.

Another useful revealed preference measure is the Treasury Department’s Series I savings bonds. These retail securities adjust their interest rate twice a year to compensate for changes in inflation, making them particularly attractive during inflationary periods. As the figure below shows, demand for I bonds surged during the recent inflation surge. While purchases have declined from their peak in July 2023, they remain well above pre-pandemic levels and indicate continued public concern about inflation.

Policy Implications

Taken together, the updated evidence largely affirms the central thesis of my earlier post: the public psyche was deeply scarred by the pandemic-era inflation surge and that scar continues to shape how households perceive and respond to inflation today. While some indicators have improved at the margin, they remain well above pre-pandemic levels. This suggests that inflation expectations, though no longer in crisis, are still fragile and easily unsettled. And that matters—because when expectations are this sensitive, even modest price shocks, such as those likely to emerge from the trade war, can complicate the Fed’s ability to maintain a credible nominal anchor. In short, the inflation scarring has not fully healed and that reality should be front of mind for policymakers as they confront the next round of inflationary pressures.

So what can the Fed do? At a minimum, the Fed needs a framework that allows it to look through negative supply shocks while still maintaining a credible nominal anchor. As I have argued many times, that is precisely what nominal GDP level targeting (NGDPLT) offers. By focusing on the growth path of nominal income, NGDPLT sidesteps the real-time knowledge problem of distinguishing supply-driven from demand-driven inflation. It stabilizes aggregate demand and keeps inflation expectations anchored without overreacting to temporary supply shocks. Even if the Fed does not formally adopt NGDPLT, it should regularly cross-check its policy choices against the forecasted path of nominal GDP. Doing so would help ensure that policy remains appropriately calibrated in an environment where inflation sensitivity remains elevated.

Bonus Content

In this short video clip, Mark and I discuss why it is unlikely that hyperinflation will come to the United States of America.

"Anchored infation expectations:" Aren't TIPS the best indicator? Granted Treasury ought to give us a 1-, 2-, & 3-year TIPS just as it should a marketable Trillionth.

“By focusing on the growth path of nominal income, NGDPLT sidesteps the real-time knowledge problem of distinguishing supply-driven from demand-driven inflation.”

_All_ inflation is “demand driven.” Sometimes the Fed’s motivation for driving target inflation above target will be supply shocks and sometimes demand shocks. The class of shock is not important for how much (height/duration) is needed to facilitate adjustment to the perturbation of relative prices.

Audio! :(

I'll wait for the transcript. :)